Balance

Life balance means we experience a harmonious blend of the different life domains. In contrast, a lack of life balance means we devote more attention to one or more life domains at the expense of others. A common life domain that many of us tend to devote too much attention to is work. Life balance is a matter of paying attention. To have a balanced life, we must divide our attention between the various important life domains.

Life Domains: Life domains are the different areas of our daily environment. Our environment is divided into many different domains, including relationships with our partners and friends, sports involvement, leisure activities, environmental practices, job/career, financial situation, political behavior, and so on; in essence, it is our direct day-to-day physical reality.

What are the most important domains in your life? Knowing your most important life domains provides you with a wide range of options for finding valuable resources and solutions. For example, the friendship domain may be a great source of support and inspiration during challenging times. Likewise, spending more time on leisure activities can be a powerful way to restore life balance when overinvestment in the work domain occurs.

It is common to become overly focused on the life domain with which we are least satisfied. However, we can become so focused on trying to gain control over a certain problem/issue that we devote little or no time to other meaningful life domains, such as friends and family. Importantly noted, focusing on only one life domain can cause us to form our self-identity predominantly around this domain (e.g., “I am a basketball player” or “I am a student”). Expanding awareness to other life domains can assist us in restoring the balance between life domains and broaden the scope of our self-definition.

Reflection Questions

- What are the most important needs you seek to satisfy in life domain X?

- What life domain needs the most attention?

- Which needs are currently satisfied in life domain X?

- Which needs are not currently satisfied in life domain X?

Point of Exploration

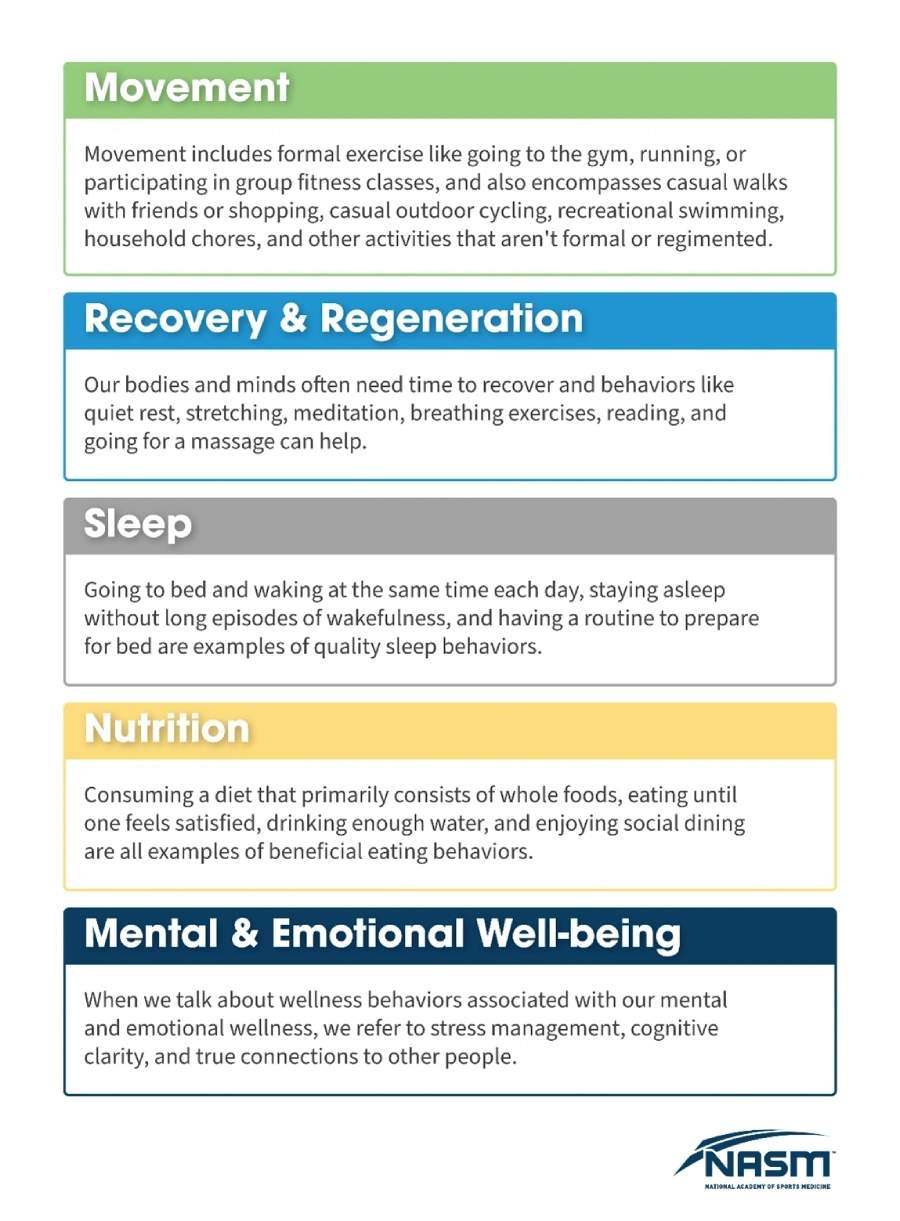

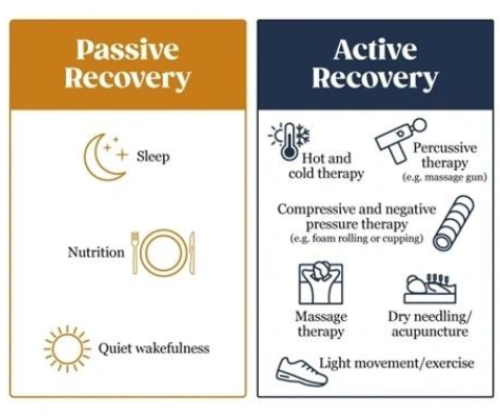

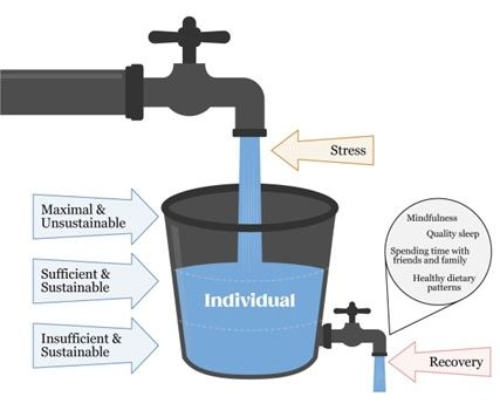

Life domains are vast for our curiosity, interest, engagement, and personal growth. Balance has to do with finding stability between our stressors and our ability to cope. It also has to do with the various dimensions of wellness and ensuring that we are seeking equilibrium between them all. For example, too much attention to exercise and too little focus on recovery is a recipe for overtraining and physiological dysfunction. This holds true for those who have incredible, nutrient-rich meals but live a sedentary lifestyle and get inadequate sleep. The imbalance between the components of the NASM domains of wellness needs to be addressed so that the figurative wellness wheel rolls smoothly.

Movement

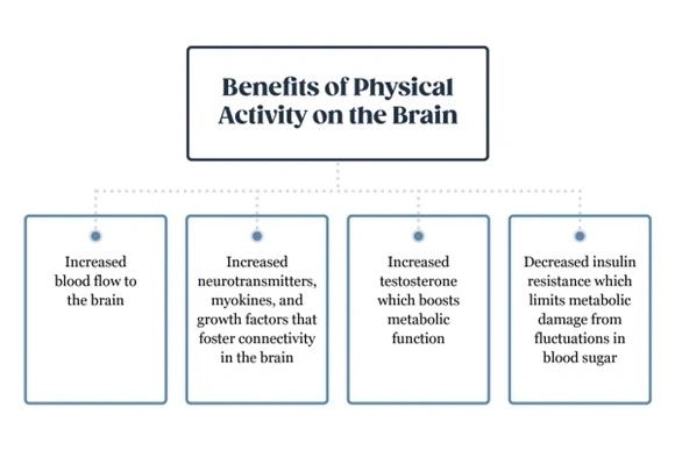

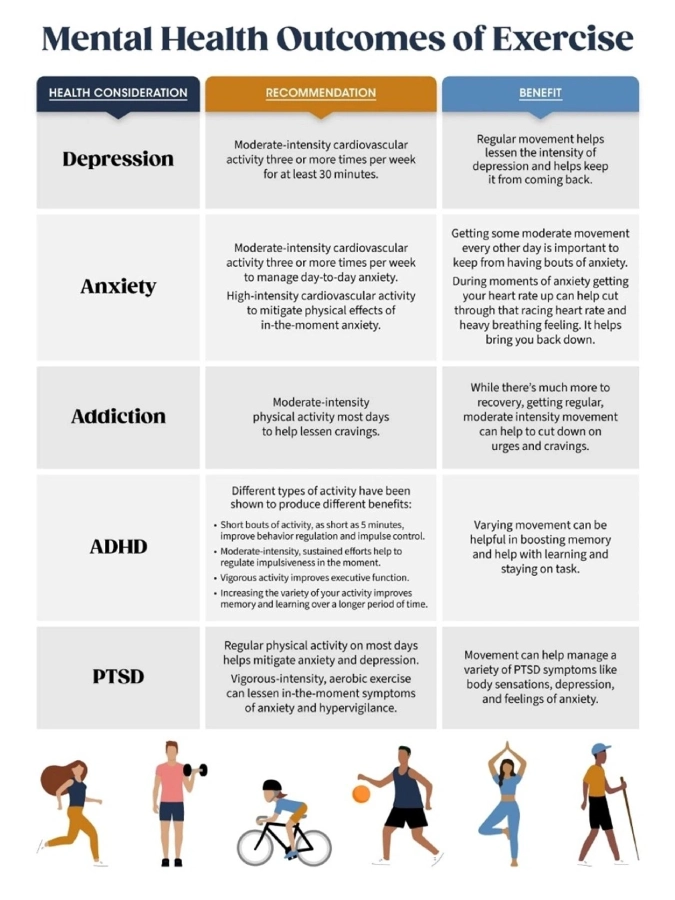

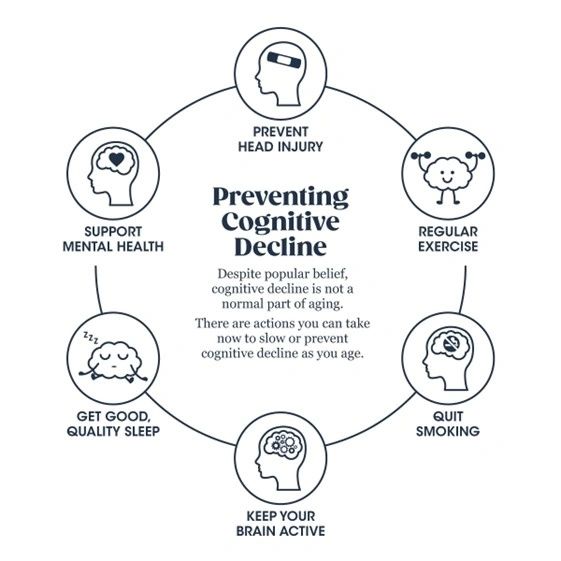

Physical activity provides protective benefits by increasing neuroplasticity, creating new tissues and the pruning of damaged tissues within the brain.

Movement has a multilayered beneficial effect on the brain. Within the cells of the brain, movement increases the density of mitochondria, the structure inside each cell where energy is made. It increases blood flow to the brain, improving the delivery system for necessary resources for brain functions. Movement also uses energy and adrenal hormones, further regulating heart rate and controlling blood pressure, thus preventing tissue damage. Different types of movement provide different benefits depending on the individual, their current condition, interest and current level of stress.

When active people become inactive, they report a decrease in positive mood affect and increase in irritability. Exercise has been shown to lesson neurological sensitivity to stress, resulting in decreased overall stress and a boost in positive emotion. Exercise actually, increases the brain’s chemistry through an increased sensitivity to dopamine and serotonin. Movement gives a boost to mood and makes the brain more sensitive to pleasure over time. Performing enjoyable movements increases the likelihood of consistency. It makes sense when you perform a healthy habit that makes you feel good emotionally, you are more likely to repeat it.

When you choose to move with others, you get more activity, enjoy it more and are more likely to continue being active. Moving together increases the feeling of belonging and trust and reduces feelings of loneliness. Regular aerobic exercise may produce the most benefit. The ability to focus, process information, creatively problem solve are all behaviors enhanced by regular movement.

Movement contributes to vitality by increasing circulation, improving metabolism, and improving sleep, all of which benefit health. Improvements to circulation increase important nutrient delivery to the tissues of the body, allowing organs, muscles, and other tissues to perform their essential functions. Improving metabolism increases baseline calories expended at rest and improves glucose sensitivity, blood sugar regulation, and overall energy availability. Increases in physical improves sleep quality, thus boosting vitality.

Self-directed movement the more autonomous and intrinsically motivated an activity is the more it will satisfy your core needs for autonomy, and competence. That means that when you enjoy an activity, or it aligns with your sense of self, you will experience more wellness, and positive emotion. You are then more likely to be consistent, which will improve your health and build lasting benefits. Self-directed actions, those which you decide on your own to do will have a strong positive influence on your ultimate goal results.

3 Ways to Discover Meaning in Movement:

1) Focus on how movement makes you feel and how it makes you feel about yourself.

2) Work toward movement milestones and creating those self- defining movement memories.

3) Find a movement community.

Recovery & Regeneration

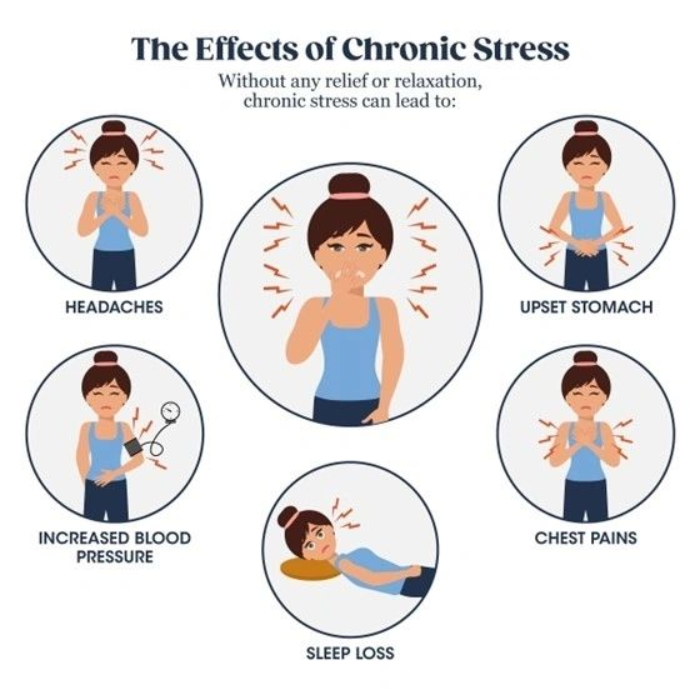

Predictability and Controllability: When the body senses disruption, the stress system is designed to respond. Consider that stockbrokers working on Wall Street make decisions every day that can result in wealth or bankruptcy. Nurses and doctors working in the Emergency Room work long hours, often during the night, and are responsible for saving lives. Professional athletic coaches might make high salaries, but with that salary comes expectations of winning games and championships. These are all high-pressure jobs. Why is it that some people thrive under such circumstances while others develop anxiety disorders, ulcers, hypertension, or depression?

Part of the answer may lie in biological differences in the stress response system. Another significant factor to consider is how psychological variables can modify the biological stress system. For example: the way in which you interpret a situation can alter emotionality in ways that can make all the difference. 2 important psychological factors shown to control the stress response are predictability and controllability.

Predictability: Research has shown that when given a warning signal, the body responds in a less stressful manner. However, over time, the brain associates warning signals with stress, so we know when to be alert and, importantly, that we are safe the rest of the time and do not need to feel on edge. In another study researchers found that in the absence of any physical stress, the lack of predictability by itself is stressful (Kirby, 2018).

What are the implications of these findings? Lack of predictability often translates into a chronically enhanced stress response, which can suppress immune function and potentially harm your nervous system. People generally like to follow a routine; so, it is best to build predictability into your daily life. Importantly noted: an action plan that follows an organized routine with clear expectations works well, but not to the point of being inflexible.

Directing Attention & Mindfulness Training focuses on strengthening attentional control and bringing awareness to current thoughts. Across a large number of mindfulness training studies, stress has less effect on working memory and attention control in people who receive mindfulness training. These protective effects have been demonstrated in many groups that experience high levels of stress, including pre-deployment U.S. military firefighters, collegiate athletes, and college students. The protective effects on working memory and attentional control are due to decreased negative mind wandering (NASM, 2023).

Mindfulness appears to be beneficial for controlling attention under periods of stress. When you are either experiencing stress, or are going to face stress in the future, it is a very beneficial practice. Remember: mindfulness exercises your brain’s attention muscles. This helps you improve your awareness of the present, which reduces negative mind wandering and improves resilience to stress.

Sleep

Movement is a common recommendation to improve sleep. Physical activity positively affects sleep and people move more when they are less sleepy, creating a positive feedback loop between physical activity and high-quality sleep. Movement improves symptoms of mild and moderate disordered breathing while sleeping, enhancing sleep quality, and benefiting overall health and wellness. When exercising within 1 hour of bedtime, there is an increased body temperature at time of sleep, longer time to fall asleep, and increased waking after sleep occurs.

Sleep has many health and wellness benefits, especially if it has been a low priority in the past. Independent of any other changes, sleeping 7 to 9 hours will not only give you an almost instant mood boost, it will also provide long-term mental and physical health benefits. Remember: sleep is free and one of the largest returns on investment of your time.

It is common to struggle with sleep due to the demands and stressors of daily life. Preparing for nightly sleep ahead of bedtime can help. Establishing a routine is critical to obtaining quality sleep.

One of the most important sleep hygiene strategies: establishing consistent sleep and wake times.

Sleep efficiency – This is the ability to fall asleep easily, stay asleep, and wake up feeling refreshed and rested.

Good sleep hygiene is absolutely essential for stress management. When you sleep well, you are better able to experience and to manage emotional things that happen to you during your day. Without adequate sleep, emotionally instability often ensues.

When frustrated by a lack of progress, it may be helpful to remind yourself that improving behaviors and skills is closely tied to rewiring of the brain. Improvements happen over time, after repetition of behaviors and sequences, and importantly require adequate sleep. In addition to feeling well, a good night’s sleep also benefits your learning and memory processes, including motor learning. Good quality and quantity of sleep allows your brain to reinforce the skills or habits they you’re learning.

Brain cleaning: Part of the reason the brain does not appear to be very active during NREM sleep is so that it can focus on “taking out the trash.” Neurons are energy hogs that produce more metabolic waste than other cells in the body. All this energy-hungry brain activity that occurs during the day results in a buildup of protein waste products. Normal aging leads to the buildup of harmful proteins in the brain. There is a bidirectional relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and sleep. Poor sleep can worsen the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, but Alzheimer’s disease also decreases sleep quality.

Memory consolidation, a central function of sleep is to consolidate memories. Memory consolidation is the process through which learned information becomes stable, long-term memories. Memory consolidation can even be thought of as “sleep dependent” because sleep is primarily the time when you consolidate new memories. Sleep, and especially deep sleep is the time when the brain takes out trash and prevents the

buildup of metabolic waste products. The time that a you spend asleep is critical for repair and restoration of brain processes. A well-rested brain is also a clean brain.

We learn and practice new motor tasks all the time: For example, how to play the piano, learning movement sequences in a sport, learning how to type, or even learning a controller movement in a new video game. A person can improve right away at these newly learned motor movements. Importantly noted, when that person sleeps that night, these recently learned motor sequences will be replayed and strengthened. This new memory consolidation will be most strongly strengthened during the later periods of REM sleep

Emotional processing, another critical function of sleep is to help you process and regulate emotions you experience during the day. This includes the consolidation of emotional memories. REM sleep deprivation decreases the ability to retrieve emotional memories. In fact, people who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have increased REM activity, suggesting that they might have “over-consolidation” of an emotional event. Proper REM sleep is essential for processing emotions.

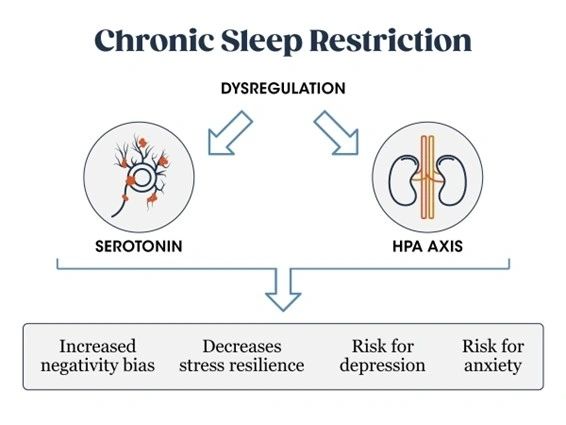

REM sleep deprivation leads to increased emotional reactivity the next day. REM sleep is particularly important for allowing the brain to discriminate between threatening and non-threatening stimuli. Without this ability, emotional reactivity can become unstable and unpredictable. That is, more things that happen during the day may be perceived as a threat to the brain. This leads to a hypervigilant individual who may be more irritable or react to the events of daily life with disproportionate and overreactive responses. Because, there is increased REM sleep density in the late night and early morning: waking up too early can be particularly detrimental to emotional memory consolidation and cause emotional reactivity the next day. Importantly noted: waking up too early can interferes with processing emotions. Increased cognitive vulnerability, sleep restriction interferes with daytime performance by impairing multiple aspects of cognitive functioning. Executive function processes are particularly vulnerable to sleep loss.

Increased risk of neurodegeneration: Another way that chronic sleep restriction can impair brain health is through an increase in neurodegeneration. Neurodegeneration occurs when nerve cells in the brain (neurons) lose their function and/or structure. Neurodegeneration is progressive and happens in several diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (neurodegeneration caused by repetitive head trauma over time).

Consequences of sleep restriction: Acute sleep deprivation is defined as greater than 24 hours of sustained wakefulness. As you might imagine, staying awake for a full day immediately affects your ability to think clearly and pay attention. With acute sleep deprivation, there is a drastic decline in concentration, alertness, and attention that can only be restored through adequate sleep. Remember, acute sleep loss also affects physical training performance, most notably energy systems required for endurance. The recovery time from acute sleep loss is typically 2 to 3 days.

The negative consequences of sleep loss, typically arise from chronic sleep restriction rather than sleep deprivation. In other words, most people rarely experience total sleep deprivation, but rather purposefully restrict their sleep time on a regular basis to meet the demands of daily life. For example: a person might go to bed around midnight and wake up a 6:00 a.m. during the week and sleep late on the weekends. Chronic sleep restriction has damaging effects on brain health and general wellness. It is associated with a 10 to 12% increase in all-cause mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011).

Can you catch up on sleep? In general, required sleep needs can be debited or credited, similar to a checkbook. Sleep debts require repayment through quality sleep of a required duration (e.g., sleeping 6 hours requires 9 hours of sleep the following night). In contrast, sleep credits (e.g., sleeping greater than 9 hours a night, termed sleep extension) can help an individual maintain concentration, alertness, and attention under acute sleep loss. Of course, this is not meant to promote skimping on sleep. It takes extra time to recover from missed sleep. Also, chronic sleep loss weakens the immune system while increasing the risk for certain diseases. Remember, if you have a poor night of sleep, you can make up for it by going to bed a little earlier or sleeping in the following night.

Nutrition

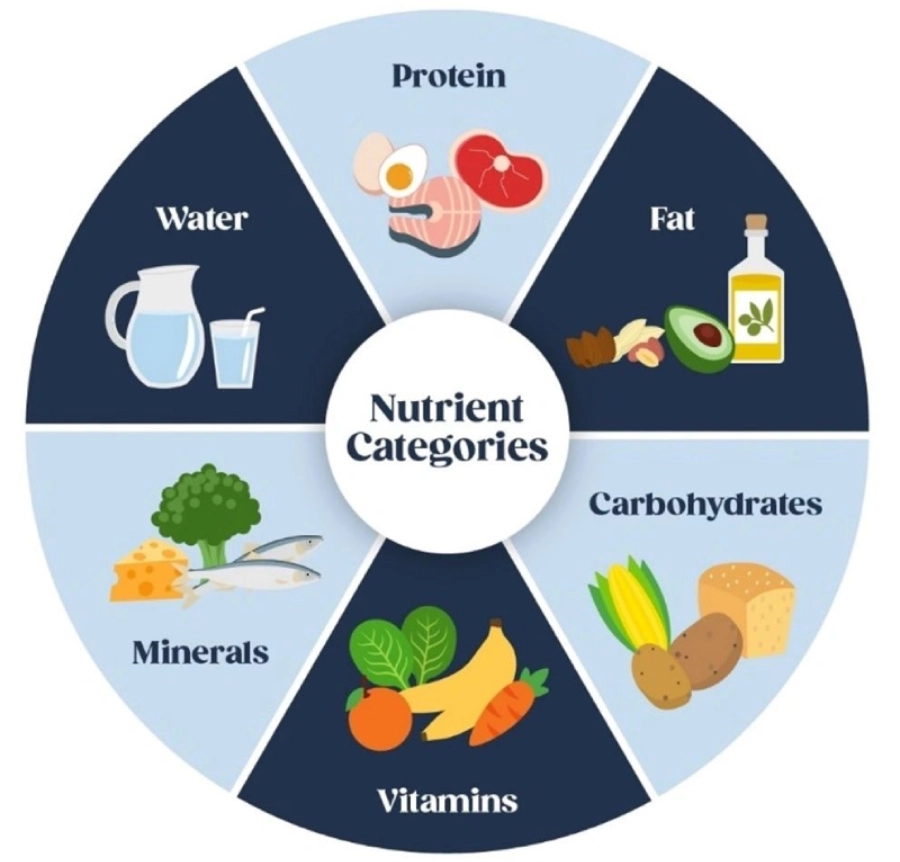

The term dietary pattern describes the overall diet, the food groups, individual foods, and nutrients included, their combinations and variety, and the frequency and quantity in which these foods, food groups, and nutrients are consumed. Good nutrition not only improves physical wellness, but it also has the potential to completely change your life in every domain. Nutrition influences emotional and psychological health, and it plays a vital role in living an enjoyable and meaningful life. A healthy, varied diet (i.e., one with foods from various food groups and containing a variety of different nutrients) can help protect you against developing a nutrient deficiency and its resulting problems. However, some dietary patterns may increase your risk of specific nutrient deficiencies, even if you have a healthy diet overall. For example: while vegan diets provide many health benefits, they are also more likely to lead to vitamin B12 deficiency unless you supplement vitamin B12.

A healthy diet is an eating pattern that considers nutritive value, physical health, mental and emotional wellness, food cost and availability, personal preferences, and cultural sensitivities. Importantly noted: a diet is truly healthy if it considers all aspects of health and wellness, not simply the nutritive value.

Nutritive value: The nutritive content of food is all the substances that are in it which help you to remain healthy (i.e., provide nourishment). Example: To say "the food was low in nutritive value" would specify that food has relatively small amounts of nutrients that provide positive health benefits.

Relationship with food: Our relationship with food is a separate consideration from the nutritional value of the foods we eat; it is comprised of the reasons why we eat, what we choose to eat, how we choose to eat, and how we feel about what we eat. A poor relationship with food is characterized by feeling compelled to stick to strict (often arbitrary) diet rules and/or experiencing negative emotions in response to eating (e.g., feeling guilty after eating, or having anxious feelings about food choices).

6 Examples of Thought and Behavior Patterns: that may be an indicator of a poor relationship with food include the following:

- Guilt – Feeling guilty about eating a particular food, meal, or amount of food

- Anxiety – Feeling anxious or distressed thoughts and emotions because of what other people may think of your food choices

- Disordered eating – Patterns of binge eating or other disordered eating patterns

- Avoiding eating intuitively – Using an external tool, such as a calorie tracking app, to determine when to stop eating or how much to eat rather than basing food decisions on hunger and satisfaction

- Demonizing foods – Completely avoiding or restricting foods due to a self-classification of those foods as bad

- A preoccupation with food – Constantly thinking about the next meal(s)

Overeating can occur in response to thoughts, feelings, and emotions. You can reduce overeating by exercising flexible restraint, rather than rigid restraint. Flexible restraint involves not viewing nutrition in all-or-nothing terms (called dichotomous thinking); instead, it is being able to eat without feeling the need to stick to strict diet rules at all times. A flexible mindset decreases the likelihood of experiencing negative emotions after eating an unplanned food or meal.

- Flexible dietary restraint: Dietary approach where foods are not labeled as good or bad and an appropriate amount of foods can be eaten without feelings of guilt.

- Rigid dietary restraint: Dietary approach where food is labeled in all or nothing terms such as good or bad.

Enjoyment of food: Another aspect of eating that can influence your overall wellness and health is the inherent joy you receive from eating. Certain meals and foods can benefit your wellness from the pleasure and enjoyment they bring you and/or by allowing you to avoid feeling deprived or restricted. When we only view foods through the lens of their nutritional value and classify them as good or bad on that basis, we fail to acknowledge food as one of life’s pleasures. Beyond just the pleasing taste of a food, this enjoyment also relates to gathering socially to eat, the cultural significance of the meal, or the nostalgic quality of a meal. Food rules that are excessively restrictive of foods or meals that fulfil these enjoyable functions is problematic and may cause harm to overall wellness.

Eating for wellness versus eating for performance, the most important dietary factors for promoting health are not necessarily the same as the most important dietary factors for athletic performance or for aesthetics (i.e., getting very lean or maximizing muscle mass). In each case, what someone would do to reach their goal may be based on different nutrition principles.

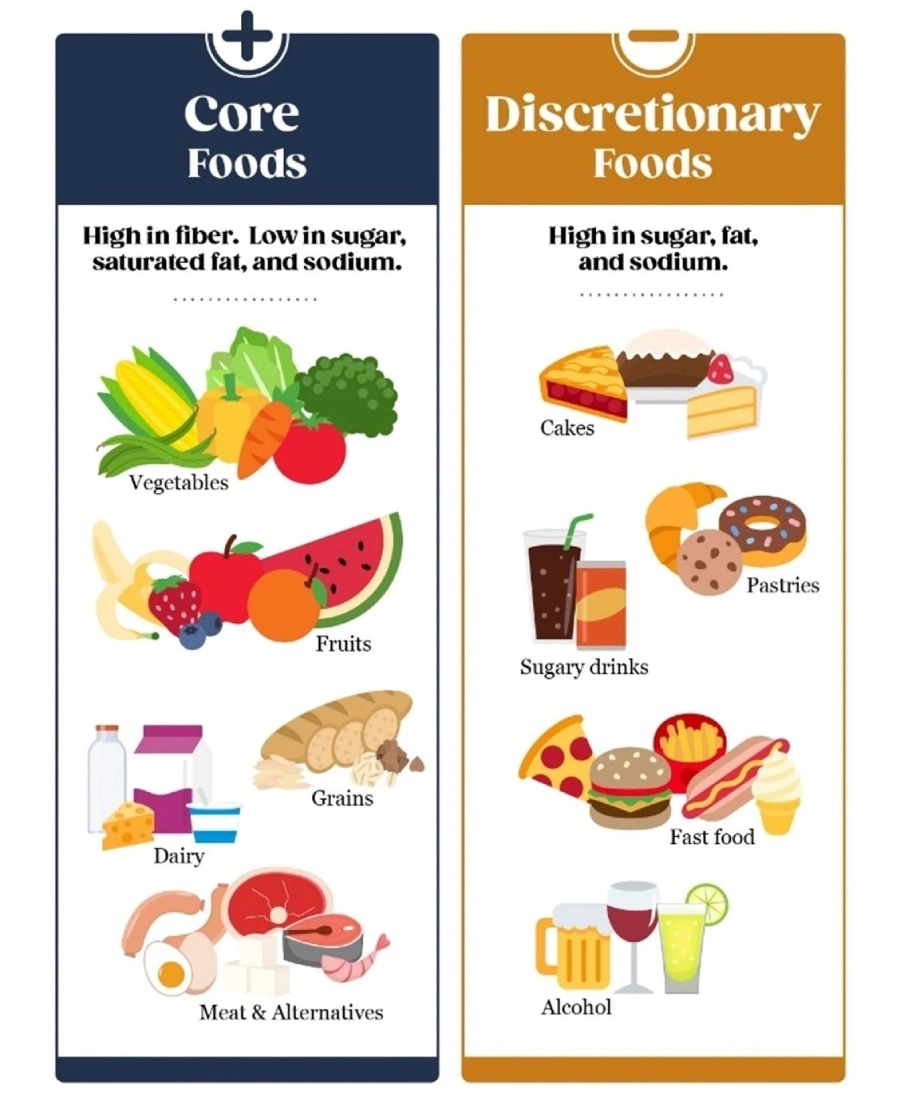

Eating for wellness is about creating a pattern that promotes good physical health, reducing the risk of chronic lifestyle-related diseases, and promoting positive psychological wellness. When your priority goal is to maximize physical and psychological wellness, your nutritional focus should be on overall diet quality. This includes healthful food components (e.g., fiber, polyphenols, and micronutrients) and avoiding restrictive food rules or mindsets that are psychologically damaging. To accomplish this, focus on what groups of foods are generally health promoting. The exact amounts of macronutrients in the diet are less of a concern, as humans can be healthy on a wide range of macronutrient intakes.

Remember the 5 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020):

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize and enjoy nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect personal preferences, cultural traditions, and budgetary considerations.

- Focus on meeting food group needs with nutrient-dense foods and beverages and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit foods and beverages higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium also limit alcoholic beverages.

- The goal is to have a varied, healthy diet that fits these principles. You can have a varied diet by selecting nutrient-dense foods from various food groups that promote health.

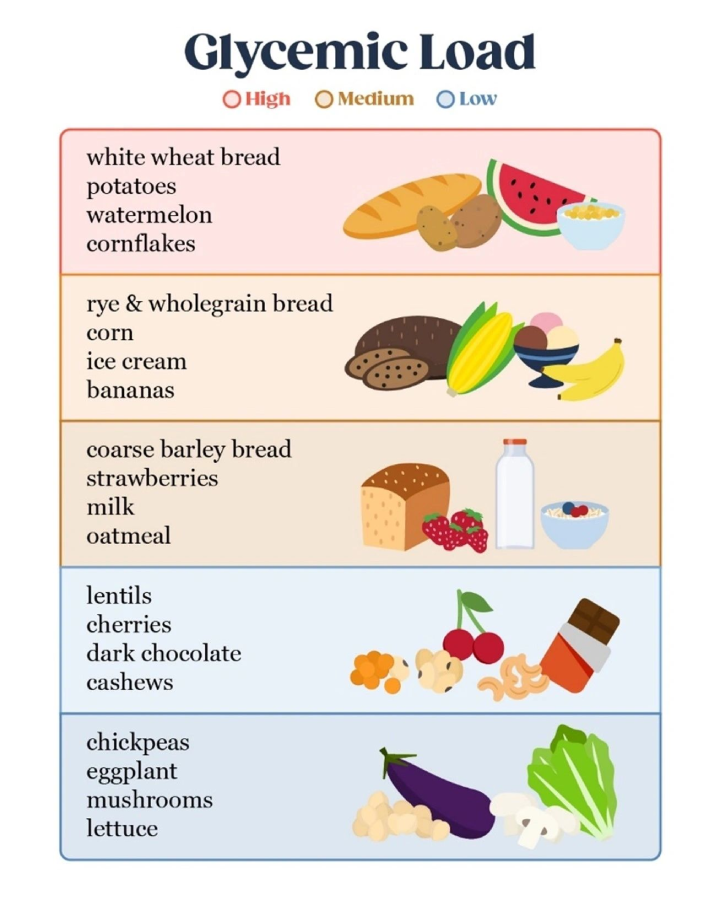

For those who need to focus on glycemic control (e.g., those with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes). These individuals should be following the advice of a registered dietitian.

Blood glucose

Commonly referred to as blood sugar: this is the concentration of glucose in the bloodstream. A healthy body regulates blood glucose within a narrow range.

Examples of Dietary Patterns

The most well-studied dietary pattern is the Mediterranean Diet, this dietary pattern is defined by similar characteristics: abundance of plant foods, emphasis on grains and legumes (couscous, pasta, polenta, bulgur wheat, breads, or beans), olive oil as the primary source of dietary fat, dairy products (particularly cheeses and yogurts), fish and poultry in moderate amounts, and regular (but low to moderate amounts) of wine.

Similar healthy dietary patterns as the Mediterranean Diet can be seen in the Nordic region, with the Nordic dietary pattern characterized by greater intake of berries, oats and rye, cabbages and root vegetables, mushrooms, and rapeseed oil (canola oil in the United States). The Nordic diet is associated with significant benefits for blood pressure, blood cholesterol, blood glucose, and body weight regulation. There are also a number of regions of the world associated with longevity and healthy aging, such as Okinawa, Japan. The Okinawan diet provides an example of a traditionally regional and healthy dietary pattern consisting largely of root vegetables, mainly sweet potatoes (which account for nearly half of daily energy), soybean-based foods, legumes, vegetables, and moderate amounts of fish.

While these diets reflect the healthy dietary patterns of specific regions, the first dietary pattern developed specifically for use as a dietary intervention was the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, which emphasized targets for servings of vegetables, fruit, low-fat dairy, fish, nuts, and legumes and replaced red meat with poultry The DASH Diet was designed specifically to reduce blood pressure, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Mindful Eating is a key component of eating intuitively, although it is not exclusive to intuitive eating. Mindful eating encourages awareness of the sensory stimuli (taste, smell, texture, etc.) of the food you eat and being conscious of your present experience of the meal. This way of eating includes the following practices, or you can remember the acronym: B.E.E.P.

- Being present (in the moment) when eating

- Eating on purpose

- Eating without judgement

- Paying attention to the food being consumed

The Center for Mindful Eating (2021) uses the following definitions:

Mindfulness: is the capacity to bring full attention and awareness to one’s experience, in the moment, without judgment. Mindful Eating brings mindfulness to food choice and the experience of eating; it helps us become aware of our thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations related to eating, reconnecting us with our innate inner wisdom about hunger and satiety.

In order to practice mindful eating: as it is defined, there must be no target of weight loss. Mindful eating is an approach that is weight-neutral. Approaches that have a mindfulness component seem to be most effective in tackling issues such as binge eating, emotional eating, and eating in response to external cues.

Mental & Emotional Well-Being

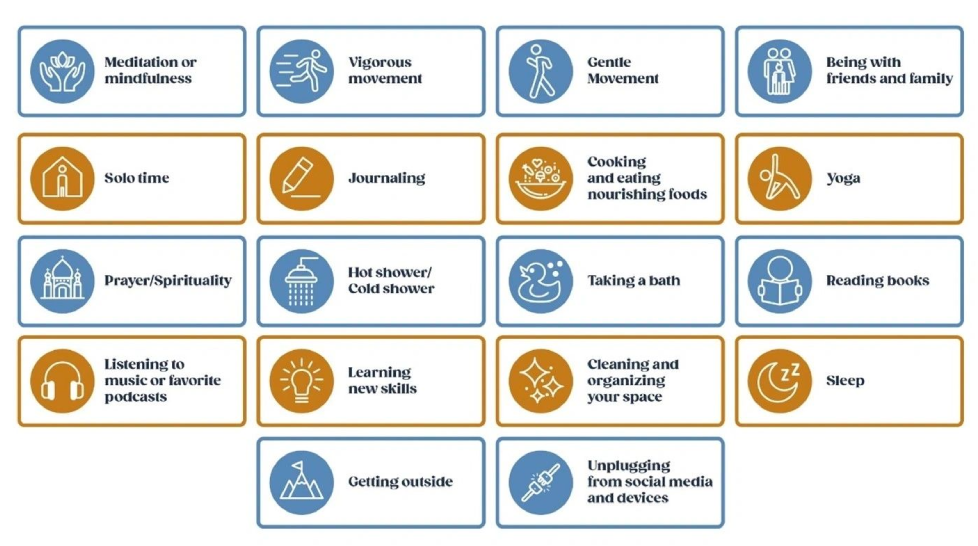

Self-wellness practices that contribute to your sense of emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being.

3 Ways of Promoting Mental & Emotional Well-Being, Remember the Acronym P.U.G.

1) Positive Self-Talk

2) Growth Mindset

3) Utilize the Permanent Vitality acronym

4 Mental & Emotional Wellness Questions to Reflect Upon…

1) What is your current relationship to sleep?

2) What is your current relationship to stress?

3) What behaviors and actions contribute to your sense of emotional wellness?

4) What makes it difficult to engage in those behaviors or actions?

Motivation and Goal Setting

Mindfulness appears to be beneficial for controlling attention under periods of stress. When we are either experiencing stress, or are going to face stress in the future, it is a very beneficial practice to utilize. Remember this: Mindfulness exercises our brain’s attention muscles; this helps us improve our awareness of the present, which reduces negative mind wandering and improves resilience to stress.

Mindful Eating, one strategy that is helpful for those who experience stress or have a habit of eating while distracted is mindful eating; it involves the practices of paying attention to physical sensations of hunger, stomach fullness, taste satisfaction, and food cravings, and the identification of emotional and eating triggers.

Habit Formation, Most goals are not achieved overnight. Long-term goals require persistent action to be accomplished. A powerful way to maintain steady goal progress is by taking consistent steps. By repeating goal-directed behavior, new habits can be formed and maintained.

“A clear purpose will unite you as you move forward, values will guide your behavior, and goals will focus your energy.” – Kenneth H. Blanchard

The effect created by a slight but consistent change in behavior (chunking) is similar to the effect of shifting the route of a boat in the illustration by just a few degrees. Rather than rigorously turning the steering wheel, the captain may instead adjust the course of the boat slightly but consistently in another direction. At the beginning of the journey, a small change in the boat’s direction is barely noticeable. However, after a longer period of sailing in this new direction, the boat’s course and thus the destination drastically change (notice the green circle in the illustration).

Importantly noted: We tend to underestimate the value of making small improvements daily, falsely believing that to reach our goals, we have to take more drastic forms of action. Consequently, we often experience a fear of failure or notice that it is simply impossible to keep performing drastic actions and changes.

The reality is there are limits to the number of concepts that can be held in our minds at one time, therefore the fewer we hold in our thoughts at once the better. When we are able to reduce complex ideas to a couple of concepts, it then becomes much easier to manipulate and remember the concepts in our minds. The ability to simplify complex concepts into their essential elements is a positive habit that the majority of highly successful business executives have utilized. This ability to simplify and breakdown concepts is a skill, aka chunking.

The following experiment is an example of chunking: Take 10 seconds to memorize these 10 digits: 1659326541. How well did you do at this little experiment…was it easy? Next, try memorizing a new set of digits for 10 seconds, 2134176594, but for this set, do it by chunking the numbers into pairs, for instance “twenty-one, thirty-four,” etc.: 21 34 17 65 94. If you timed yourself, you would quickly become aware of how much simpler and efficient it is to memorize the second set of numbers. The size of the chunk of information roughly correlates to the amount of time it takes you to say each item, in this case, numbers. Importantly noted, the most efficient chunks of information take less than 2 seconds to repeat out loud or think about. The fact is, the human brain wants to chunk information anytime we reach the limits of what can be effectively processed and retained.

Chunked change: a linear approach of consistently engaging in the same, low dose of goal-directed-behavior for an extended period of time, for example, it least 3 months.

Identity-Based Motivation: The repetition of behavior shaping our identity has important implications for the development of new habits. It suggests that the stronger a new habit becomes, the greater its power will be to change one’s perceived self-view. Consider a person who aims to quit smoking. At the beginning of the habit formation process, his/her identity may still be that of a smoker who is trying to quit. However, over time, when the new habit of non-smoking has become an inherent part of his or her life, this identity may be replaced with the new identity of a “non-smoker.” Likewise, the person who starts exercising three times a week may, after a year of consistently exercising, start to perceive themselves as a healthy person. His or her initial “I’m trying to get healthier” may slowly evolve to “I am a healthy person.” Habits, when formed successfully, can have a transformative and long-lasting effect on behavior. Remember: the more our identity reflects who we want to be, the more motivated we become to maintain the habits associated with it. The reality is, the formation of new habits can be a virtuous cycle where a shift in identity becomes a strong motivator for sustaining goal directed habits.

Even a slight change in daily habits can have a great effect over time. For example, writing a book, although writing 30 minutes on the first day may not seem to make a significant difference, however writing for 30 minutes consistently every day for two months will contribute considerably to goal progress and achievement.