The Significance of Motivation in Goal Setting

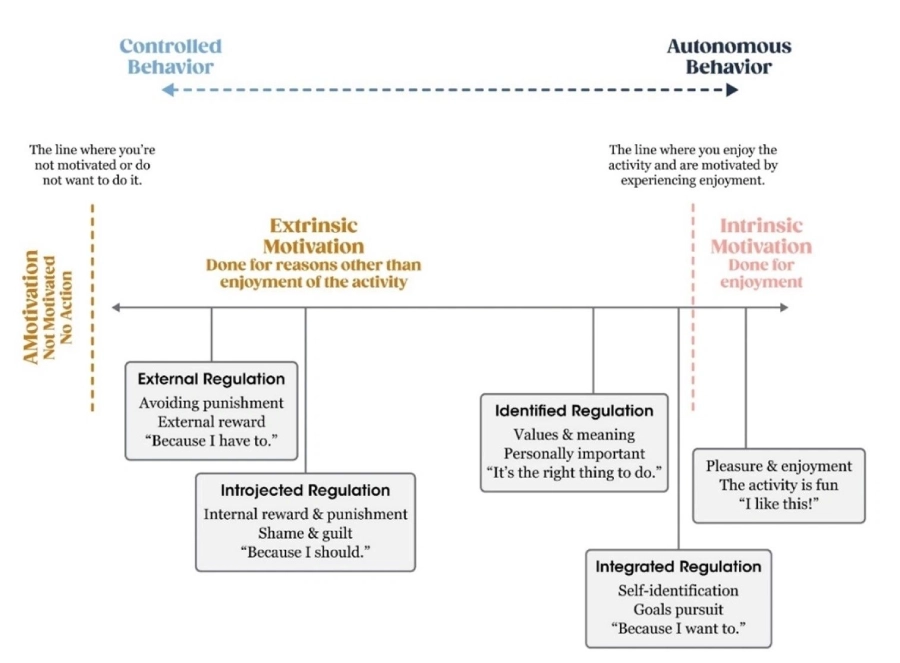

Take a look at the range of underlying reasons and factors for controlling human behavior.

At one end of the continuum is motivation, in which a person feels no desire to perform a given behavior. Their behavior is not regulated because they have little interest or see no importance in the activity, habit, or behavior. For example, this is a person who does not exercise, does not wish to exercise, does not think about exercising, and does not consider physical activity to be a priority.

At the other end of the continuum is intrinsic motivation, where the activity, habit, or behavior is made entirely for the pleasure of doing it. Intrinsically motivated behaviors require little self-regulation because doing that activity is its own reward. These activities are enjoyable for the creativity, learning, engagement, and joy present in performing them. For example, someone who loves the feeling and outcomes of physical activity is intrinsically motivated. They have built a life that includes dance, yoga, sports clubs and teams, hiking, biking, and everything in between. They do not think of this activity as exercise because it is just what they do and is part of what they enjoy.

Motivation is about needs:

Needs are essential elements of growth. Examples of needs include the need for food and shelter, the need for connectedness with others, the need for freedom of speech, etc. Needs are an important source of human motivation. For example, our need to belong motivates us to stay in touch with others, our need for autonomy motivates us to make our own choices, and so on. By becoming aware and assessing our level of motivation for concrete action and the needs underlying the motivation, we can increase the chance that the desired changes we seek will effectively promote wellness and vitality.

Identified Motivation: In goal pursuit that is driven by identified motivation, the actions needed to accomplish the goal are perceived as personally important and meaningful. In some instances, these goals have been taught by others. However, when guided by identified motivations, we endorse them freely and value them enthusiastically. For example, a person might aim to exercise daily to be fit enough to play with his or her grandchildren. Identified motivation can be viewed as value-based motivation, where personal values are the main drivers of goal pursuit.

Connecting goal pursuit to personal values is a means to increase identified motivation, thus focusing on the “why” of our goal-directed behavior.

Autonomous Actions: Behaviors in which we choose to act under our own volition – this may be out of enjoyment of the behavior because we identify with the behavior internally or the behavior aligns with our personal values and goals.

The topic of motivation is a multifaceted one; in short, it’s an “intangible variable that ebbs and flows widely in short periods of time.” Athletes with seemingly unparalleled drive lose it. Some people show up to practice one day with a fire lit inside them, and the next day, the motivational fire has fizzled out. From week to week, teams, athletes, coaches, and workers fluctuate in their intensity and level of dedication.

Motivation at a foundational level represents a tendency to pursue, engage, and persist in activities related to your chosen interests and goals. In essence, it is the direction and intensity of the effort you put forth to successfully complete a given task. Direction indicates what you pursue, and the intensity is how much effort you put forth (refer to inserted images to see this concept in action). As another example, you could make a choice to attend practice over a social event (direction suggests that you are motivated); however, you proceed to kid around with teammates throughout practice (intensity suggests lack of motivation).

Direction indicates what activity is pursued (in the above picture, Lucy, the basset hound, is pursuing one of her favorite pastimes, napping; in the picture below, we see a group of athletes in pursuit of the finish line). The other component of motivation, intensity, is about how much effort is being exerted toward the activity being pursued (in both pictures, maximum effort is being exerted toward reaching a desired goal; in the picture above, the desired outcome is sleep, whereas, in the picture below, the goal is winning the race, or setting a personal best record).

It is essential to look at both aspects (direction and intensity) in an effort to better understand motivation, but it is equally important to note that motivation is a complex concept and that motivation will vary from individual to individual and also across situations from one individual to the next.

The word motivation is derived from the Latin word “movere,” meaning “to move,” and describes the often-powerful inner voice that activates you to direct your behavior in a specific fashion. Synonyms include “desire,” “get-up-and-go,” “zip,” and “oomph.” Whatever you choose to call it, motivation is clearly a key component of performance; without it, you are never fully psychologically ready to compete or complete the task at hand.

It is important to remember a key function of motivation is to adjust one’s personal goals in ways that improve one’s possibilities to manage one’s current life situation. Individuals who have difficulties in making this adjustment are incapable or unwilling to change their previous goals and are at greater risk of feeling unhappy. Additionally, feelings of well-being and happiness are likely to influence the types of goals that individuals create.

Motivational influence is essential to your daily life. A complete absence of motivation equals inertia, no activity at all. This is an unnatural state for human beings because we all possess a deep-seated need to explore and master our environment to help our own survival. Thus, nobody is completely devoid of motivation. What we sometimes need to discover is the key that unlocks our own motivational spirit. Our motivational spirit is the “fuel” that will fulfill our potential.

Motivation involves the ‘why’ of our choices. For example, “Why do I wish to reach this goal?” or “Why is it important for me to stay in touch with this person?” To understand the impact of motivation on our well-being, it is important to consider ![]() key ingredients of motivation:

key ingredients of motivation:

1) Autonomy: The more autonomous our motivation is, the more it reflects our values and interests. Higher levels of autonomous motivation can be summarized as “want to” and lower levels as “have to.” In general, higher levels of autonomous motivation have more of a positive impact on wellness than lower levels.

2) Needs: A need is something necessary for you to live a healthy and happy life. Examples of needs include rest, safety, and autonomy. Needs are an important source of motivation. For example, our need for rest motivates us to take a day off. Becoming aware of our needs helps us to better understand the ‘why’ of our choices.

Action:

“While intent is the seed of manifestation, action is the water that nourishes the seed. Your actions must reflect your goals in order to achieve true success,” said Steve Maraboli.

Action refers to concrete behavior. Action is about what we do. For our wellness to increase, it is not enough to become aware of things. We need to follow awareness and insights with concrete actions. To improve well-being, it is important to address ![]() forms of action:

forms of action:

1. Past Actions: Our past actions provide valuable insights into patterns that have been helpful or unhelpful. Unhelpful actions of the past can serve as a lesson, preventing us from making the same mistake in the future. Helpful actions of the past can serve as a guide, teaching us what has worked well for us. Such insights can be translated into concrete actions.

2. Current Actions: Reflecting on our current actions is essential for continuous growth. On a regular basis, we must ask ourselves whether our current actions support a meaningful life and are true to the person we want to be; this reflection helps us to become aware of any discrepancies between our ideals and our actions.

3. Future Actions: Planning future actions helps us to concretize unclear intentions and allows for more concrete results. For example, rather than saying, “I want to live a healthier life,” planning concrete future actions, such as, “I’m going to run on Thursday morning,” increases clarity and the chance that we will take action.

Why is the concept of control so important to setting goals?

The concept of control in goal setting is of the utmost importance because setting realistic, attainable performance goals is within your control. When you possess control over your goal achievement, you are able to focus on your performance, often leading to subsequent outcome goal attainment, thus realizing your mission and vision.

Commitment: To realize your potential somewhere deep in your core, you must choose to go after your dreams. You also have to create and firmly establish an underlying belief that you can accomplish your goals. The plan is to nourish your focus, your confidence, long-term commitment, and belief in your mission statement. The fact is, dreams do not become a reality unless you act in ways that make them a reality.

Awareness: Gaining awareness is the first fundamental step in goal setting. Goal setting requires awareness because you must first establish your goals, then make every effort to reach them, then proceed to evaluate performance feedback, and finally adjust the goals as necessary. When you gain more awareness, you make accurate adjustments in your goal pursuits. This ability to adjust the subtle details of performance is a vital skill to have as you pursue your goals.

![]() Ways Utilizing Goals Are Important to You:

Ways Utilizing Goals Are Important to You:

1) Goals direct your attention and effort toward goal-relevant activities and away from goal-relevant activities.

2) Goals have an energizing function; high-level goals lead to greater effort than low-level goals.

3) Goals affect persistence. When you control the time you spend on a task, challenging goals prolong effort.

4) Goals influence action indirectly by leading to the discovery and/or use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies (Kirby, 2018).

“A clear purpose will unite you as you move forward, values will guide your behavior, and goals will focus your energy.” – Kenneth H. Blanchard

Goal Setting Obstacles:

Goal Setting Obstacles:

1) Creating too many goals too soon

2) Not taking into account individual differences, as there’s not a one-size-fits-all approach to goal-setting

3) Creating goals that are too general

4) Staying the course with unrealistic goals

5) Setting only outcome goals

6) Not fully understanding the time commitment

7) Not being able to create a supportive goal-setting environment can greatly impede goal (s) accomplishment.

Importantly noted, goal-setting obstacles can easily be avoided if you are able to recognize them at the beginning of the goal-setting process.

Remember the power of accountability in goal setting: Accountability means taking the necessary steps to daily monitor and keep track of what was done, what happened, what worked, what did not work, and what you may want to do differently in the future. Accountability increases confidence, and confidence fuels motivation!

Assertiveness is an effective strategy that can be utilized to assist you in achieving your goals is being more assertive; this is an important characteristic for achieving success and is defined as “the honest and straightforward expression of one’s thoughts, feelings, and beliefs.” Usually, when people are not assertive, it is because they lack confidence. The more assertive you are regarding your concerns, struggles, progress, and accomplishments, the more likely you are to achieve long-term success, reaching all of your goal destinations (Kirby, 2018).

“Nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs.” – Henry Ford.